The following essay provides the aspiring Chicago Metro History Fair participant with some background, perspectives, and sources on New Deal art. It focuses specifically on mural art, but many of the questions, sources and information could be applied to other forms of artistic expression. In sum, it suggests three ways to approach the study of New Deal art in Chicago:

- Content Analysis (art history). Investigate and analyze themes in the murals.

- Policy (political history). Examine the creation and implementation of government-sponsored art programs in the 1930s.

- Chicago area artists (biography). Explore the careers and lives of some of the artists who worked on government-sponsored art projects.

Chicago, The Great Depression and the New Deal

Few Americans escaped the economic devastation wrought by the Great Depression. From 1929 to 1933 investment fell 87%, production levels were cut in half, and unemployment rose to 25%.1 The employment situation was far worse than the numbers suggest because the jobless rate did not count the millions of underemployed Americans, including those suffering severe wage cuts or employed in seasonal work. Estimates suggest that at the depth of the Depression, one-third of employed workers had only part-time work.2 As an industrial city boasting steel mills, meatpacking, and electrical manufacturing plants, Chicago felt the blunt force of the failing economy. In 1932, thousands of stockyard workers clogged streets in the Back of the Yards neighborhood in a demonstration calling for government relief.3 Chicago thus provides a rich laboratory for Depression and New Deal era studies.

Students wishing to investigate Chicago and the Great Depression or New Deal have an infinite number of topics and sources upon which to draw. Some may be interested in exploring the experience of a group of people during the Depression—African Americans, women, laborers, children, or immigrants, for example. Others may prefer to examine family life, or some aspect of politics. They may wish to evaluate the effect of a New Deal policy, such as the National Industrial Recovery Act, National Labor Relations Act, or Social Security Act on the lives of ordinary Chicagoans. Among the many New Deal policies directly affecting ordinary individuals were those designed to provide work relief for the unemployed.

Like his predecessor, Republican President Herbert Hoover (1929-1933), Democratic President Franklin D. Roosevelt (1933-1945) did not want to put Americans on the “dole,” a derogatory term used to describe direct cash relief. Roosevelt felt that unemployed Americans did not want a hand out, but a hand up. In order to preserve their dignity and offer them a psychological boost, Roosevelt advocated for New Deal programs that put Americans back to work. During the first 100 days of his administration from March to June 1933, Roosevelt supported the creation of a Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), which employed young men in a wide variety of environmental projects. Also enacted in the first 100 days, his Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA) dispensed funds to state-level administrators for local public works projects. In 1935, he signed into law the Emergency Relief Appropriation Act, which provided for the establishment of a Works Projects Administration (WPA; later renamed the Works Progress Administration). Over the course of its existence, the WPA employed 8.5 million people in vast public works projects.4 WPA workers not only built schools, bridges, hospitals, park lodges and furniture, but they also made art. Chicago area residents benefited directly from these programs.

Chicago and New Deal Art

Project One of the WPA consisted of four programs designed to provide unemployed artists with work. The Federal Art, Music, Theater, and Writers Projects, like most New Deal programs, were joint federal-state-local initiatives. The Illinois Federal Art Project employed over 700 artists, including sculptors, painters, and printers. Although the art project was a statewide initiative, its heart and headquarters were in Chicago. Consequently the Illinois Art Project, and specifically, the Project’s production of murals make it an ideal topic for students wishing to study the Great Depression and New Deal in Chicago. Not only does the Center for New Deal Studies contain a wealth of information on the WPA programs, but also Chicago schools and other buildings hold a treasure trove of New Deal era murals, many produced for the WPA. Between 1935 and 1943, the Illinois Art Project produced approximately 316 murals, although some of those have not survived.5

Not all of the New Deal-era murals produced for Chicago-area building were done under the auspices of the WPA. The Civil Works Administration, created under the 1933 National Industrial Recovery Act, set up the Public Works of Art Project (PWAP), considered the first federally sponsored art program. This program, run by Edward Bruce with technical direction by Forbes Watson, supported 3749 artists and created 15,633 works of art.6 Artist Edgar Britton, for instance, painted nine PWAP murals for Highland Park High School.

Edgar Britton, “Scenes of Industry” panel (1934), Highland Park High School, Highland Park, Illinois

Starting in 1934, the Treasury Department commissioned artists to create paintings, sculptures, and architectural designs for federal buildings through its “Section of Painting and Sculpture” (often referred to as “The Section.”) Section artists painted many of the murals found in local post offices. Unlike Federal One, artists working for the Section did not have to be on relief roles and their pay was higher. Instead artists competed for these commissions through a selection committee.

Investigating Government-Sponsored Mural Art of the 1930s

Student may choose to approach the topic of Chicago New Deal mural art by focusing on one or some combination of the following three topics:

- Content Analysis (art history). Investigate and analyze themes in the murals. For instance, what do the murals say about gender, class, race, ethnicity, and/or national/regional/local identity?

- Policy (political history). Examine the creation and implementation of government-sponsored art programs in the 1930s. What kinds of controversies arose over these programs in Chicago and what do they tell us about Depression Era Chicago and America?

- Chicago area artists (biography). Explore the careers and lives of some of the artists who worked on government-sponsored art projects. How did government work inform their artistic expression, how did it affect them personally, and how did it shape their careers?

Content Analysis

Download the Mural Analysis Worksheet (PDF, 7K)

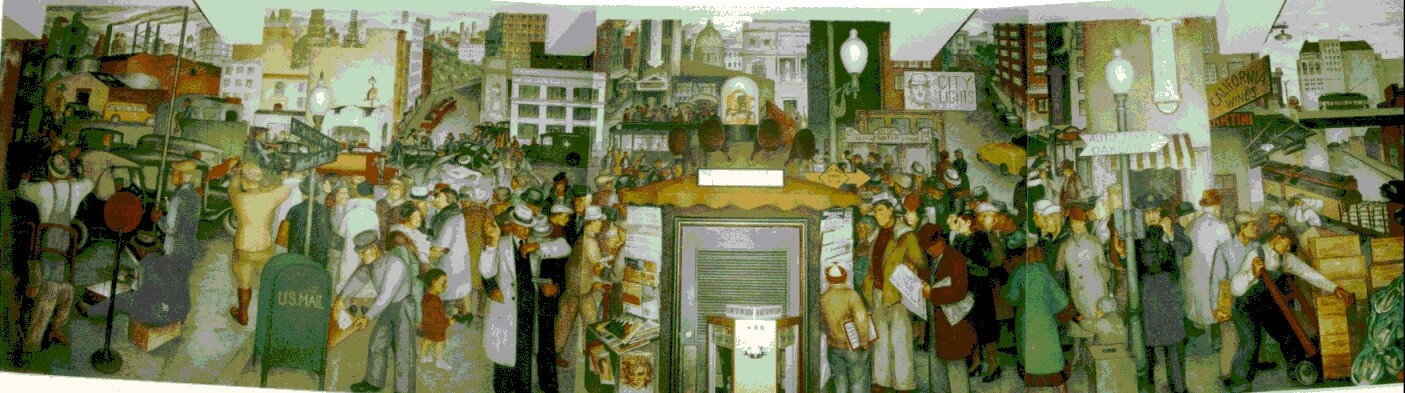

Chicago’s New Deal murals provide us with insight into the assumptions, ideals, and politics of Americans in this era. They reflect a new emphasis (begun in the 1920s) on the creation of distinct American art. Many of the works celebrate patriotism, upward mobility, technological progress, the work ethic, and cooperation. During the 1930s, the “American Scene” achieved prominence, reflecting an interest in regionalism. Paintings that suggested a strong sense of place, such as a small town square, skyscraper, streetscape, or farm conveyed the importance of geography in American life. Many of the PWAP murals adorning the walls of San Francisco’s Coit Tower illustrate this theme. Victor Arnautoff’s 36 foot-long mural, “City Life,” is an excellent example of the American Scene:

Victor Arnautoff, “City Life,” (1934), Coit Tower, San Francisco, California

Questions: How does Arnautoff’s mural "City Life" evoke a sense of place? Which places? What kinds of images does he use to suggest local, regional, or national themes? How would you describe San Francisco after seeing this mural?

Questions to pose for Chicago area murals: Do Chicago-area murals reflect the American Scene tradition? If so, what does it say about life in Chicago, Illinois or the Midwest? Does it accurately depict life in the city/region or is it an idealized vision?

Other artists chose subjects that conveyed a sense of “Social Realism.” Social realists focused on conflict in American life. Artists aimed to expose social, political, and/or economic inequities in the hope of inspiring people to work for reform. Some concentrated on racial discrimination, others on economic inequities, and still others on the contentious relationship between man and machine. These questions may help guide your analysis of social realist murals: What kind of conflict is portrayed in the artwork? Was the conflict or problem a severe one in 1930s Chicago or America? Does the scene suggest a solution to the problem? How does the artist seek to make the viewer care about the issue presented?

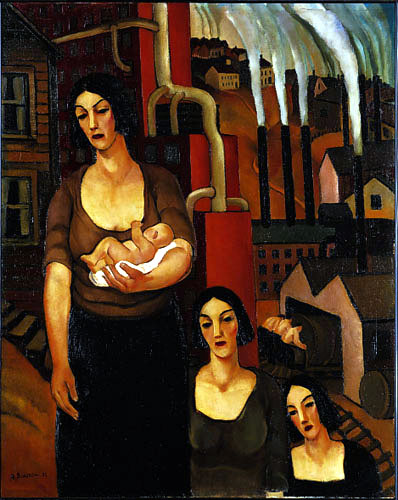

This painting, “Industry,” by Arthur Durston done for the PWAP in 1934 reflects ambivalence toward industrial progress:

Arthur Durston, “Industry,” (1934)

While artists working for the WPA’s Illinois Art Project painted in a variety of styles, suggesting the influence of cubism, Mexican mural art, surrealism and abstraction, many of them painted subjects that reflected their experiences in Chicago. As a major industrial city, Chicago attracted large numbers of immigrants, who formed the backbone of the city’s working class. Chicago workers developed strong union traditions and many Chicago painters felt a responsibility to be similarly socially and politically engaged. Some used their art as a commentary on social injustices. Look for patterns in the subjects chosen by Chicago muralists. Do the subjects speak to a particular social problem in the city? Why and how does the style highlight the importance of social activism?

An evaluation of a piece of work gains in depth the more one learns about the context in which the art was produced. For instance, while none of the program administrators directly censored the art produced under them, there were clear preferences and some rules about the art. Administrators frowned on abstract art and forbade nudes. A successful analysis of the artwork itself will require some understanding of the Depression, the New Deal, and the 1930s in general.

Sources: Of course, the murals themselves are primary documents. But other primary documents such as personal memoirs, newspapers, trade journals, magazines, and published pictures of lost murals should supplement these rich sources. And, as mentioned in the last paragraph, a wealth of secondary sources will provide necessary background.

Policy

Students interested in politics and public policy may prefer to discuss the ideologies, social forces, and economic considerations that shaped the creation and implementation of New Deal art programs. In many respects, Federal One represented a typical New Deal program in its insistence upon the sharing of responsibility between federal, state and local authorities. Nervous about the growth of a large and centralized national government, many Americans felt more comfortable with government programs that dispersed power across various levels of government and through numerous agencies. Some students may develop arguments about the nature of federal power exercised by the WPA, and Federal One in particular. How did President Roosevelt and Federal One administrators envision the Illinois Art Project? Did their vision reflect a particular worldview or political sensibility? Did it make a statement about the role of the federal government in the lives of individuals or in the creation of a “national” identity? Did the Illinois administrators, such as Art Project directors Increase Robinson, George Thorpe, and Fred Biesel, facilitate artistic expression or impede it? Did the program foster democracy or represent the rise of a “big government” that encroached upon individual artistic expression? Any of these questions would provide the basis for a stimulating research project.

Some historians combine social and political history by examining policies from the “bottom up.” One of the professed aims of Federal One was to make art accessible to the masses. Was it successful in this endeavor? How did ordinary people experience the art programs? Were the artists employed by the program assisted materially and/or psychologically? Did they perceive themselves as workers or employees of the federal government or as independent artists? What kinds of controversies swirled around the Illinois Art Project? Did race, gender or class conflict and ideologies influence the administration of the project?

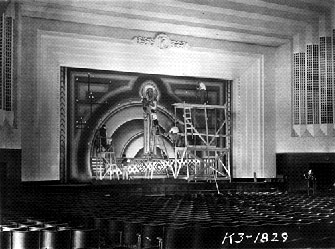

Muralists at work, Lane Tech High School, Chicago, Illinois

Policy historians often find a wealth of information through published government documents, such as government hearings (a wonderful source of viewpoints because they give voice to many of the participants in the program), bills, statutes, and the Congressional Record. Other possible primary sources include newspapers, trade journals, magazines, manuscript collections, and published memoirs.

Artist biography

Another way to approach the study of government-sponsored art is to delve into the lives of the artists who created it. This approach has the advantage of personalizing the art and giving further insight into the art produced.

In a number of cases, the Illinois Art Project launched the careers of painters and muralists, and in other instances it sustained already established artists through the dire years of the depression. Sometimes, a particular artist captures the interest of a historian. Chicago muralists included Frances Badger, Aaron Bohrod, Edgar Britton, Gustaf Dalstrom, Florian Durzynski, Roberta Elvis, Frances Foy, Ralph Hendricksen, Thomas Jefferson League, Edward Millman, Archibald Motley, Jr., Mitchell Siporin and Rudolph Weisenborn. Some overcame significant social barriers, such as race, ethnic and gender discrimination, to become successful artists. Students may want to analyze these barriers and discuss how the individual either hurdled them or became constrained by them. Or, students may become intrigued by one person’s artistry and thus analyze the style, content, and nature of that person’s murals.

Some historians engage in the construction of “collective biography.” In this approach, the historian focuses on categorizing artists into groups and then discussing common experiences among members of the group (and perhaps differences from other groups). These experiences may then be used to get a more sophisticated understanding of the mural art.

Sources: Information on the lives of individual artists can be obtained from newspapers, city directories, biographies, memoirs, and personal and organizational manuscript collections.

The topic of New Deal art in Chicago provides opportunities for those interested in social, political and/or cultural history to delve into the process and meaning of federally-sponsored artwork. Of course, Chicago had rich artistic traditions long before the federal government undertook this endeavor during the Great Depression. Nevertheless, federal dollars and a deep well of creative talent encouraged an outpouring of art in Chicago. For seasoned and new historians, there is much to discover.

Margaret Rung

Director, Center for New Deal Studies

Associate Professor of History

Roosevelt University

1 Thomas K. McCraw “The New Deal and the Mixed Economy,” ed. Harvard Sitkoff, Fifty Years Later: The New Deal Evaluated (New York: McGraw-Hill, 1985), pp. 38, 40; David Kennedy, Freedom from Fear: The American People in Depression and War, 1929-1945 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999), p. 163.

2 Kennedy, Freedom From Fear, p. 87.

3 Lizabeth Cohen, Making a New Deal: Industrial Workers in Chicago, 1919-1939 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990), p. 1.

4 Kennedy, Freedom from Fear, pp. 252-53.

5 Heather Becker, Art for the People: The Rediscovery and Preservation of Progressive- and WPA-Era Murals in the Chicago Public Schools, 1904-1943 (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2002), p. 84.

6 Thomas Thurston, “The New Deal and the First Federally Sponsored Art Program: The Public Works of Art Project (PWAP) 1933-34” in Becker, Art for the People, pp. 74-75.

Questions about this page?

Questions about this page?

Director Center for New Deal Studies